The Ethical Implications of Gene Editing in Embryos: Where Do We Draw the Line?

Of course, many factors come to bear upon the extent of disease eradication which gene editing can achieve. As yet no-one has arisen who can answer conclusively how long it will take for these advances in medical technology to result in change and end suffering diseases such as cystic fibrosis. At best though, surely they may bring hope nearer home at last.

The age of sophisticated genetic design is dawning. Today, researchers have made a major break-through in editing embryonic genes: “For the first time,” claimed UO scientist Etienne Michon, “we can actually change the very stuff that makes up life’s blueprint.”

We hope to spread across the world the wonderful benefits of gene editing inside people, rendering even potently toxic conditions such as AIDS no match for our scientists. The prey in all this is disease and suffering replaced by fluid, liquid health systems in favor of cancer control policies that could scarcely have been imagined not long ago.

But gene editing in embryos raises many ethical issues, even if it offers tremendous benefits. One of the most important questions is: who will decide what counts as a desirable genetic trait. Editing genes to prevent disease may appear clear cut but if that very same technology also enables non-medical enhancements like greater intelligence or beauty, athletic ability–things get very tricky indeed.

On Autonomy and Consent

The chief ethical problem is whether or not something new will be coming up out of the ground in defiance of nature. Embryos cannot give informed consent to genetic alteration, the effects of which go on throughout their life.

If parents who carry such genes can also pass them on to their children, future generations might have to bear the consequences.

Autonomy questions get mixed up with the matter of whether or not our descendants have the right to inherit an intact genome.

On Equity and Access

Secondly, gene editing has the potential to aggravate existing social inequalities. So long as it remains expensive and available only to the wealthy, there is a danger of creating a genetic underclass against which an elite upper stratum will develop with powers no one else can match. The “genetic divide” might therefore serve only to deepen class or ethnic divisions.

On Safety and Unintended Consequences Error! Hyperlink reference not valid.

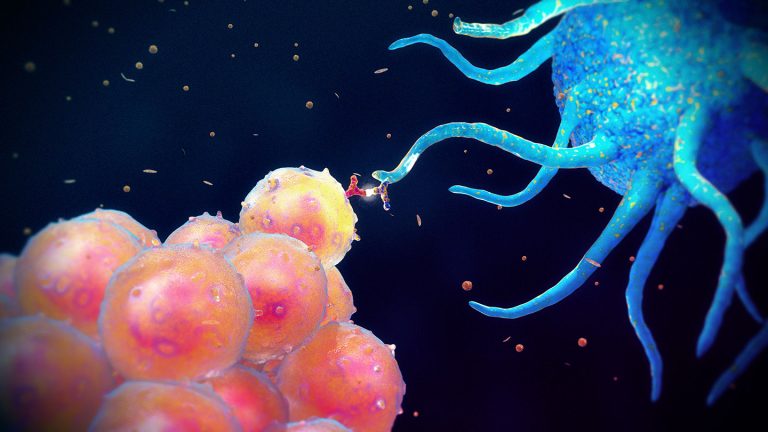

Long-term safety of gene editing is still unknown. Off-target effects that modify unexpected parts of the genome could lead to unknowable and potentially dangerous results.

Moreover, with human germline editing these genetic changes made in infancy will be inherited by the person’s descendants, generation after generation unless corrected for an error.

These points mean that reassurances on safety become even more necessary.

The Role of Regulation

Finally, robust national and international frameworks/searches are needed to address these ethical problems. Body such as the World Health Organization have called for an international moratorium on heritable genome editing until we know much more about the ethics, social implications and it’s safety. At the national level, governments should also make plain their policies for controlling misuse of gene editing technology and promoting responsible scientific development.

There is much hope that embryo gene-editing could be employed as a medical treatment for a wide variety of diseases, such as Parkinson’s and cystic fibrosis. Yet because it brings human beings into the picture (1), this technology’s long-term consequences are anything but certain and its moral dilemmas are great.

Open dialog involving experts in science, ethics, policy making and the general public can help to generate consensus and trustworthiness on how this powerful technology should be used.

Another way to approach this problem is dividing therapeutic from non-therapeutic. It might be permissible by medical ethics to alter the genetic make-up of individuals so they have genes for illnesses they will never catch, or even to cure those illnesses there then with editing. But if this DNA changing is done for some purpose other than destroying disease–and especially when the point is not treatment but public display–probation against such actions is likely to harden.

But even this distinction may become blurred in practice as what constitutes “therapy” changes.

A different method would be to limit gene editing to an individual’s body cells (“soma”) rather than in the so-called germ cells, which will form new human beings. In this way issues of inheritability and long-term effects could be sidestepped while advances in medical treatment could still continue.

As society continues to evolve, we should confer and come to agreement on where this technology can belong. If that doesn’t happen, society cannot make responsible use of its power.

Balance the freedom of gene editing with moral restrictions, and we will be able to use this new technology to give everyone healthier lives while protecting the values that make us human.